|

|

(3.21) |

From The Age of the Earth, G. Brent Dalrymple, Stanford University Press, 1991, pp. 115-19. Copyright © 1991 The Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University.

One of the most powerful and reliable dating methods available is the U-Pb concordia-discordia method. It was devised in 1956 by G. W. Wetherill, a pioneer in radiometric dating and now Director of the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism of the Carnegie Institution of Washington (Wetherill, 1956). Like the Ar-Ar age spectrum, this method can be used on open, as well as closed, systems — a feature of special value for dating old rocks with complex histories — and is self-checking. The U-Pb concordia-discordia method differs from the simple isochron methods in a fundamental way because it utilizes the simultaneous decay and accumulation of two parent-daughter pairs — 238U-206Pb and 235U-207Pb.

To understand how the concordia-discordia method works, we must return to one of the simplest of the radioactive decay equations. Let us rewrite Equation 3.5 in terms of 238U and its final daughter product 206Pb:

|

|

(3.21) |

and rearrange it to express the relationship of daughter to parent as a ratio:

|

|

(3.22) |

where λ1 is the decay constant of 238U (Table 3.1). In these two equations the quantity of 206Pb represents only the amount of the Pb isotope produced by the decay of its U parent since the rock formed, so initial Pb must either be zero or be eliminated by being subtracted from the total 206Pb. The comparable equation for 235U and 207Pb is

|

|

(3.23) |

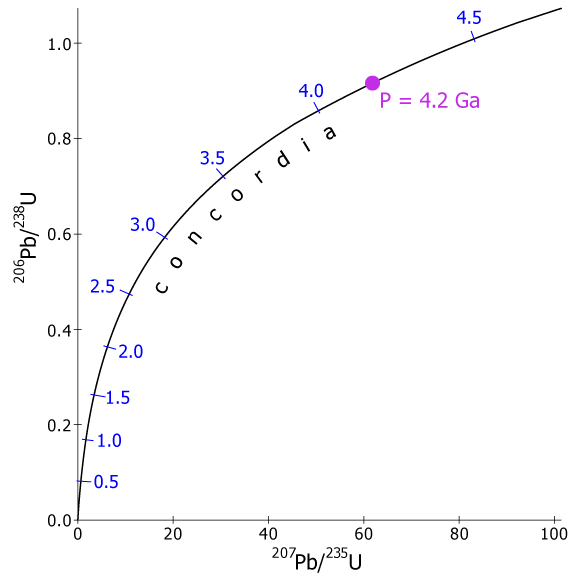

where λ2 is the decay constant of 235U. We can now substitute various values of t into Equations 3.22 and 3.23 and graph the resulting ratios 206Pb/238U and 207Pb/235U (Fig. 3.13a). These ratios for all values of t plot on a single curve called concordia, which is the locus of all concordant U-Pb ages. All minerals that formed at 4.2 Ga and have remained closed systems, for example, will plot at point P in the figure and will also have identical 206Pb/238U and 207Pb/ 235U ages of 4.2 Ga. Concordia is curved because 238U and 235U decay at different rates (Table 3.1) and so the relative rates of production of the two isotopes of Pb have changed with the passage of time.

Fig. 3.13. a) The U-Pb concordia diagram. The concordia is the locus of all points representing equal 235U/207Pb and 238U/206Pb ages. The location of a sample on concordia is a function of age; point P, for example, is at 4.2 Ga.

The graphing of concordant U-Pb data on a concordia diagram does not provide any information that is not obvious from the individual U-Pb ages themselves. The principal value of the concordia diagram is its unique ability to yield crystallization ages from open systems. Let us examine how this aspect of the method works.

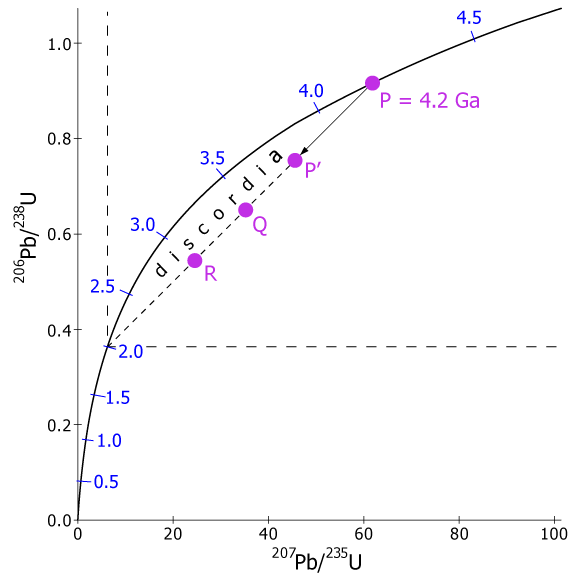

As mentioned in the section on U-Th-Pb methods, Pb is a volatile element and is rather easily lost from minerals when they are heated. Loss of Pb, however, does not fractionate the isotopes in the remaining Pb because they are chemically identical and their masses are very nearly the same. Thus, Pb loss from a mineral with a composition at point P will result in the ratios 206Pb/ 238U and 207Pb/235U changing from P to some point along a straight line connecting P and the time of the Pb loss (Fig. 3.13b).

Fig. 3.13. (b) The episodic loss of Pb moves a point, P, off concordia along a straight line (discordia) connecting P and the origin to P'. The dashed lines show the position of the origin of the graph as it would have been drawn at 2.0 Ga. At some later time (2.0 Ga later in this example) samples from the same rock Q, and R) will plot on a line whose upper intercept with concordia gives the age of the rock and whose lower intercept gives the time of episodic Pb loss.

To visualize why this happens, suppose, for example, that a mineral formed at 4.2 Ga was heated at 2 Ga and lost some of its Pb. If we could transport ourselves back in time and make some Pb and U measurements while the event was in progress, we would see P move off the concordia and progress on a straight-line path toward the origin, i.e. toward 206Pb/238U = 0 and 207Pb/235U = 0. This happens because the two Pb isotopes are lost in the same proportion as their relative compositions at P. The result of complete Pb loss would be the total absence of Pb in the sample and the composition would then plot exactly on the origin. In this latter case, the U-Pb clock would be completely reset. In Figure 3.13b, the straight line path is a line connecting P with the 2 Ga point on concordia because the origin of the graph at 2 Ga, shown by the dashed lines, was at what is now the 2 Ga point. As the 2 Ga elapsed between then and the present, the origin of the graph moved along the concordia to its present position. The Pb compositions along the ordinate and abscissa, of course, also “follow” the origin and change with time to reflect the change in the composition of Pb in the sample as well as the evolution of concordia. Thus, today point P' lies on a chord connecting P, the original age of the sample, and the age of Pb loss, i.e. 2 Ga. This chord is called a discordia.

As may be obvious, a discordia cannot be determined by a single point such as P'. We must find at least two and preferably three or more points along a discordia before we can find either the original age of the rock, P, or the time of Pb loss. As it turns out, however, this is not especially difficult. The amount of Pb lost from a sample is controlled by a variety of factors, including grain size, original crystal imperfections, composition, and radiation damage from the decaying U. Thus, different crystals from the same rock sample will lose differing amounts of Pb, so analyses of different forms (colors, shapes, sizes) of the same mineral species from a sample will usually do the trick and provide sufficient differences in Pb/U composition to define a discordia. Different minerals from the same sample, mineral separates from different samples of the same rock body, or different zones within a single crystal also can be used to determine a discordia. Thus, Pb loss from a sample at P would not only result in the point P' but would generate other points, such as Q and R, as well.

Episodic loss of Pb, discussed above, is only one of several theoretical Pb-loss models that have been proposed to explain discordia. All of the models predict that the upper intercept of a discordia with concordia is the original age of the rock, or, more precisely, the time of the last complete resetting of the U-Pb clock. The interpretation of the lower intercept, however, is not so clear and differs according to the model used, although the current weight of evidence favors the episodic model. We need not be concerned with this point, however, because the evidence for the age of the Earth does not depend on the interpretation of the lower intercept.

Like the simple isochron methods, the U-Pb concordia-discordia method is self-checking. Disturbance of the sample due to partial Pb loss leads to a discordia and permits the determination of the age of the rock. Uranium gain, if such were to occur, would have exactly the same effect as Pb loss and the data could be interpreted in the same way. The loss of U drives the point P along an extension of the discordia above the concordia and toward higher Pb-U values; the original age is still recorded by the intersection. The result of the addition of Pb to the sample is unpredictable because it depends on the isotopic composition of the added Pb.

The concordia-discordia method can be used only on minerals that contain either no initial Pb or initial Pb in such small quantities that a correction for its presence can be accurately made. Such minerals are not abundant in rocks, but fortunately there are several that occur frequently, although in only small amounts, in most igneous and metamorphic rocks. The most common is zircon, whose crystal structure accepts U but rejects Pb so that initial Pb is invariably negligible or very small. The presence of initial Pb can be detected and corrected for if necessary by using the nonradiogenic 204Pb. The crystal and chemical properties of zircon and of other minerals used in this method make U loss, or the gain of either Pb or U, very unlikely, so that Pb loss is the dominant effect of heating.

The U-Pb concordia-discordia method is especially resistant to heating and metamorphism and thus is extremely useful in rocks with complex histories. Quite often this method is used in conjunction with the K-Ar and Rb-Sr isochron methods to unravel the history of metamorphic rocks, because each of these methods responds differently to metamorphism and heating. For example, the U-Pb discordia age might give the age of initial formation of the rock, whereas the K-Ar method, which is especially sensitive to heating, might give the age of the latest heating event. There are examples of concordia-discordia diagrams in succeeding chapters.

Wetherill, G.W., 1956. Discordant uranium-lead ages I. Transactions of the American Geophysical Union, vol. 37, pp. 320-26.